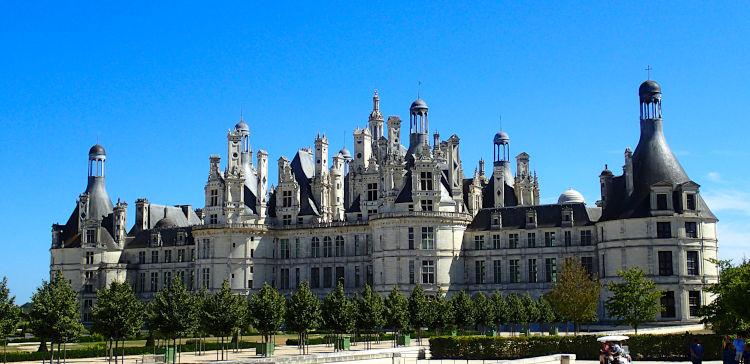

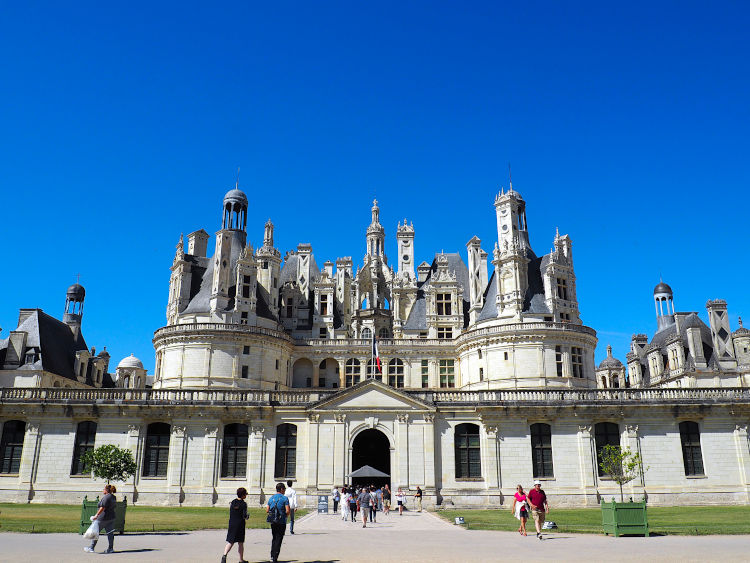

This has got to be the most magnificent chateau in the Loire Valley. It’s easily the largest chateau and it was actually built to serve as a hunting lodge for King Francis I. You could certainly invite ALL of your friends and their friends to come for a weekend and still have rooms left over.

The original design of the Chateau de Chambord has not been attributed to any particular architect, as not everyone can agree on who it was. It does, however, bear the imprint of Leonardo da Vinci in many areas of the architecture, and it’s very much thought he played his part in the design of certain elements.

Francis I, maintained his royal residences at the chateaus of Blois and Amboise. His “hunting lodge” took 28 years to build from 1519 to 1547. Francis spent barely seven weeks there in total at his hunting lodge, that time consisting of short hunting visits. He actually died of a heart attack the same year it was finished. What a bloody waste of the country’s money it must have been at the time. All that time and millions of Francs for just seven weeks holiday.

The chateau is an absolute monster of a building with the following mighty numbers:

- 440 rooms

- 282 fireplaces

- 84 staircases

- Enjoys a collection of 4,500 objets d’art displayed in superbly refurbished rooms

- It’s 6 times the size of most chateaux

- Is surrounded by 13,400 acres of wooded park and game reserve, and is teeming with wild deer and boar

- Enclosed by a 19-mile long wall.

The chateau also features 156 metres of facade and towers, more than 800 sculpted columns and an elaborately decorated roof and roof terrace. When Francis I commissioned the construction of Chambord, he wanted it to look like the skyline of Constantinople.

Of the 440 rooms of the chateau, tourists can view 60 of them. Some of those visitors complain that those rooms are empty. This isn’t really the case, although lots of rooms do have no actual furniture in. They were only rarely furnished even when the chateau was in use.

The King and the French court moved around the kingdom all the time. The decor and furnishings were sent on ahead and, when the king moved, taken out and sent on again. The monarch’s entourage might typically have numbered 2,000 people but could go up to as high as 10,000 people, with 20,000 horses. That is just incredible. Talk about how to make yourself feel important. You got 10,000 followers on Facebook, pah I’ve got 20,000 actual people who follow me around carrying my furniture!

As Chambord had been designed as a 440 room hunting lodge then it really had only been constructed with the purpose of short stays. It was not practical to live in it on a longer-term basis. The massive rooms, open windows and high ceilings meant heating was impractical. Similarly, as the chateau was not surrounded by a village or estate, there was no immediate source of food other than game. This meant that all food had to be brought with that massive group of people each time.

For more than 80 years after the death of King Francis I, French kings abandoned the chateau, allowing it to fall into decay.

Finally, in 1639 King Louis XIII gave Chambord to his brother, Gaston d’Orleans, who saved the chateau from ruin by carrying out much restoration work, particularly to the roof.

Then King Louis XIV had the great keep restored and furnished the royal apartments. The king then added a 1,200-horse stable, enabling him to use the chateau as a hunting lodge and a place to entertain a few weeks each year. Nonetheless, even after all that work and investment, Louis XIV abandoned the chateau in 1685.

From 1725 to 1733, Stanislas I, the deposed King of Poland and father-in-law of King Louis XV, lived at Chambord.

In 1745, as a reward for valour, the king gave the château to Maurice de Saxe, Marshal of France who installed his military regiment there. Maurice de Saxe died in 1750 and once again the colossal chateau sat empty for many years.

In 1792, the Revolutionary government ordered the sale of the furnishings. They even removed the wall panellings and some of the floors were taken up and sold for the value of their timber. During the public sales of those items, some of the panelled doors were burned in the fireplaces to keep the rooms warm, as Chambord was a very open and drafty place.

The empty chateau was then left abandoned until Napoleon Bonaparte gave it to his subordinate, Louis Alexandre Berthier. The chateau was subsequently purchased from his widow for the infant Duke of Bordeaux. A brief attempt at restoration and occupation was made by his grandfather King Charles X but in 1830 they both were exiled.

During the Franco Prussian war of 1870 to 1871, the chateau was used as a field hospital.

The final attempt to make use of the colossus came from the Comte de Chambord but after the Comte died in 1883, the chateau was left to his sister’s heirs, the Dukes of Parma. Seems throughout history the darned place was so huge that it was more of a liability than it was useful.

Any attempts at restoration ended with the onset of World War I in 1914. The Chateau de Chambord was confiscated as enemy property in 1915, but the family of the Duke of Parma sued to recover it, and that suit was not settled until 1932.

The Chateau and surrounding areas, some 13,400 acres (21.0 square miles) have belonged to the French state since 1930. In 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, the art collections of the Louvre and Compiegne museums (including the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo) were stored at the chateau. Restoration work on the chateau was not begun until a few years after World War II ended in 1945. There must have been an incredible amount of work to be done by this point.

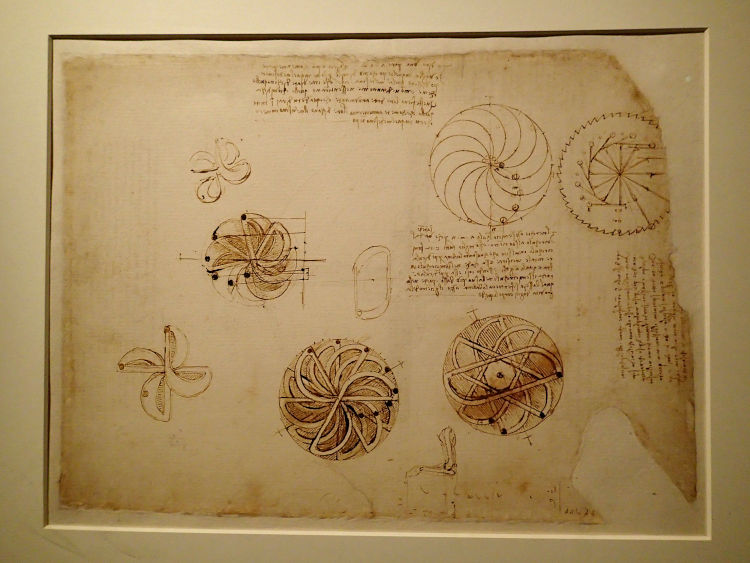

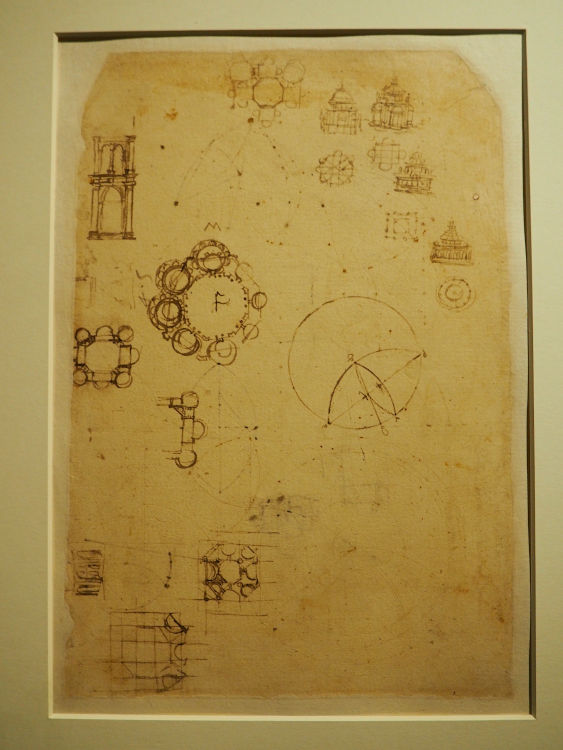

The chateau of Chambord is undeniably an exceptional achievement, influenced at least partly by the work of Leonardo da Vinci. Following the Battle of Marignan (in Italy against the Swiss) which Francis I won in the first year of his reign, he discovered the marvels of Italian architecture. More specifically he discovered the incredible work of Leonardo da Vinci. When he returned to France in 1516, he invited Leonardo to join the French court as “premier painter, architect and engineer of the king”.

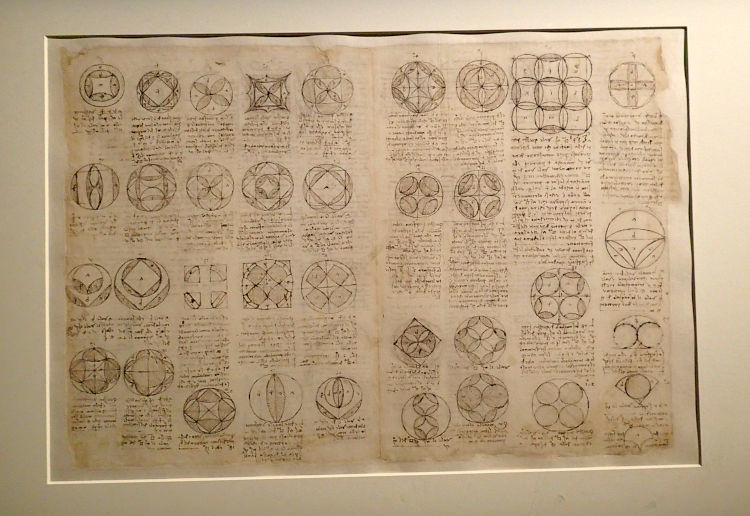

In 2019 (luckily the year of our visit) the chateau commemorated the 500 years since Leonardo died. They put on a show of original sketches by him from his notebooks. These very much match what was actually built at Chambord. The centre-plan design of the keep, the incredible and massive double helix staircase, the double pit evacuation system with its air duct and the sealing system on the terraces are telltale indications that reveal the role of Leonardo as the brain behind the work of Francis I.

We very much enjoyed seeing the original notebooks and pages penned by Leonardo. After recently walking in the footsteps of Joan of Arc and Jacques de Molay, now we can place our hand when De Vinci once sketched his intricate ideas and engineering designs.

Leonardo spent the last three years of his life in France and King Francis I had become his close friend. Leonardo died in May 1519 aged 67.

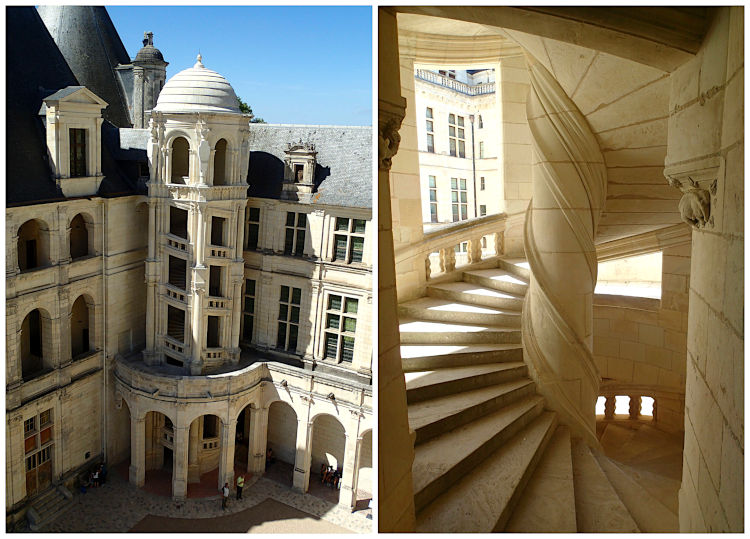

The most famous part of the chateau is Leonardo de Vinci’s engineering masterpiece, his double helix staircase, which was a revolutionary design at the time. It’s set in the centre axis of the chateau’s gigantic keep with four vastly wide corridors leading off of it in the shape of a cross, with one leading to the gardens and the other three to the inner courtyard.

The layout of the staircase is remarkable. It’s composed of twinned helical ramps twisting one above the other around a hollowed-out, partially open core. There are two staircases so there are two ways in or out on each floor. If I enter one side and Nigel enters the other, we are both on totally different staircases and can never meet – but we do catch glimpses of each other through the open center. It’s fun and beautiful.

The staircase services the principal floors of the keep, all the way up to the crowning terraces, which are topped off by the tallest tower of the castle, the lantern tower.

Ever since it was built in the 16th century, the staircase has continued to fascinate chateau visitors. If you begin climbing one staircase and your partner starts opposite at the other staircase at the same time, you can see each other through window openings in the central column but never cross paths. It’s really fascinating, an amazing feat of engineering and incredible use of space. Oh, and it’s fun too.

As you wander around the vast Chambord Chateau you will see the salamander represented more than 300 times on ceilings, walls and doors. A salamander is a small amphibian creature that is as comfortable in the water as it is on land.

This small creature was the emblem of King Francis I. He had the motto “I eat the good fire, I put out the bad “. The motto refers to the popular belief that a salamander has the power to resist flames.

It was then time for us to visit some of the rooms off of the staircase and also the royal bedrooms etc.

This was one of the kitchen fireplaces.

One of the better pieces of art.

Here’s one of a number of the royal carriages that were made and NEVER used at Chambord, which seems to sum up the extravagance and waste of the French Royalty here. No wonder the masses rose up in 1789! Their excesses were, well, excessive.

This is one of the ceremonial bed chambers that was in a vast room. The King’s Bedchamber has always been the central feature of the king’s apartment in traditional French palace design. Ceremonies surrounding the daily life of the king, such as the levee (the ceremonial raising and dressing of the king held in the morning) and the coucher (the ceremonial undressing and putting to bed of the king), were conducted in the bed chamber. The bed chamber and more particularly the bed played a singular role in French cultural history from the late Middle Ages until the French Revolution in 1789. While a throne has been associated with most European monarchies as a symbol of temporal authority, in France the throne was virtually non-existent.

Oh, we did find this throne. Not sure who ever sat on it though.

Oh and these two thrones as well. The smaller one on the right being the ancient equivalent of a bidet.

This was the bedroom of King Francis I.

And this was the Queen’s bedroom. (Wish we had separate bedrooms. Nigel snores too much)

And finally, for the tour, this was the Governor’s room, with one of those lovely beds recessed into the wall. This was such a pretty room, Deby was oohing, all around the place.

We were parked on site in the motorhome parking within the walls of the park. You get a 24hr ticket. Once we had returned to our motorhome and had a meal we waited for the sun to go down and decided to try some dusk photos. This time we photographed the main facade (the face of a building) of the chateau from across the water.

That facade and the corner towers measured 156 metres wide, a mammoth 512 feet of facade and towers.

We were very pleased with our evening photos. We think they came out splendidly. In the daytime, we weren’t able to get in position to take similar photos as we would have had to squeeze around the edge of a fence, which we weren’t really allowed to do. At night no one was there to stop us. You could wander around the whole place as much as you wanted and there didn’t seem to be any security.

All in all, we had a great day of sightseeing at Chambord. Entry fees were a total of €35.50 which got us both in with one histopad tour between us.

Our motorhome parking space for overnight parking, with no facilities, cost us €11. Not the nicest place, rather dusty, but there was easy access, lots of space, and it was an easy and pleasant walk from the parking over to the chateau. And gave us the opportunity for the lovely visit in the evening. Recommended.